Los Salvadores de la Uva in Chile

Let’s just say that Chile and I have had a sordid relationship for a while.

For years, all its wines – from the tippy top of expensive all the way to the turn-on-the-tap jug wine – have had a pesticide/new rubber-jacket aroma and flavor that haunt me to this very moment. So, when I met Giselle and Alejandro D’Apremonte two years ago, I was less than impressed. He, a former hipster-skateboarder and radio personality in Chile, and she, the brains of the partnership, were beginning their dream to import natural Chilean wines to the U.S. and were eliciting my help. As our relationship grew, and we tasted wines sent by their Chilean winemaker friends, I was really excited for these grapes and the freshness that they were expressing.

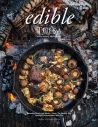

Rescue Mission

The three gateway Chilean wineries I have fixated on here have resuscitated my belief that Chileans can make really great wine: Tinto de Rulo, Cacique Maravilla and Roberto Henriquez. Each grower has latched onto the history of Chilean wine. They are rescuing some of the oldest vines in the world, with age-old winemaking at their core.

In the center of the natural resurgence is the País grape, also known as the Mission grape. Wine is made in a traditional style called Pipeño, which ferments the grape in indigenous Raulí wood barrels (5,000-10,000 liters) called pipes. Cepa País originated in Spain and came to Chile with the Jesuits via the Canary Islands. Each of the Gang of Tres sources it from Chile’s coastal range inward to the dry coastal lands where there is no irrigation. They wanted to escape modern wine styles, so looked to the past for inspiration. They vinify the same artisanal way, without using commercial yeasts or chemical corrections.They only apply a very low dose of sulfur to stabilize the wine for its trip across the water, which allows all the characteristics of the vineyard, terroir, to be put into the bottle intact.

Partners Jamie Pereira, Mauricio Gonzalez and Claudio Contreras at Tinto de Rulo in Bío Bío Valley are a work in progress. Two agronomists and one enologist don’t always agree, but once they leave their day jobs at the nameless conventional behemoth tank farm, it’s only love for the once-abandoned farm near San Cristobal that lay dormant for 30 years. The volcanic soils that elevate these varietals are from the eruptions of the Antuco Volcano, and the Mediterranean climate comes forward in their wines. The trio makes one of the most polarizing wines I have ever had from the dry farmed/non-irrigated soils known in Chilean farms as “Rulo,” a Carginan sourced from the Maule Valley. Seventy-year-old vines are planted in granite soils, yielding overwhelming bright fruit with a healthy dose of geranium. They also source Malbec fruit in the valley from a vineyard planted 200 years ago. They even make a pretty tasty País in amphora – yup, they’ve found some old, old tinajas that they’re trying ever so gingerly to move to the bodega. All the wines at Tinto de Rulo are picked and destemmed by hand. They’re never inoculated with yeast, but are allowed to start spontaneously and ferment naturally, with the only addition of sulfur at bottling and less than 15 micrograms per liter, nearly unmeasurable, allowing the intensity and delicacy of the fruit to come front and center.

Cacique Maravilla

Also in the region of Bío Bío is Cacique Maravilla, with seventh-generation wine grower Manuel Humberto Moraga Gutiérrez, who says he works naturally by principle. He makes wines as the early Spanish civilizations did, dry farmed – no watering is needed as it grows in volcanic soils and holds a great sense of terroir. Their wines express the land. All they need to do is take care of the vines by pruning in the winter and feeding with organic matter. The País Pipeño grapes, handpicked in the vineyard go into open Raulí barrels, cluster and all, which ferments with native yeasts with ambient temperature. It stays in Raulí for 10-14 days, then there are two decantations as a way of filtering naturally before it goes in the bottle.

Gutiérrez is a larger-than-life figure with a Dante-meets-Santa-Claus bearded face and his wines are just as playful. A great bargain, País Pipeño comes in a liter bottle and drinks like the Beaujolais of Chile and a Cot and Cabernet blend that will make the Bordelaise ask for more.

Back to Tradition

Roberto Henriquez, whose eponymous bodega is in Itata, might be the leader of the pack. All young winemakers in the region elicit his counsel. For such a young man, Henriquez is wrapped in tradition. Destemming is done by hand; manual cap immersion is done daily, using little or no machinery. His Pais Pipeño is not an innovation in Chilean wine, but a reflection of the country’s history. He sees challenges to independent and small wine growers in Chile, including governmental politics that help the largest wine conglomerates. He’s both angry and sad that these centennial, heritage clones are not government protected, and that the forestry business is prioritized in an unbalanced way.

Recent fires in the region have shown small farmers that they’re on their own as the government protects the forests and literally passes over the fires at the small farmers’ bodegas. Unfortunately, many of the key characters will be gone – the barrel maestros are getting older and dying along with the men and women who have taken care of these vines, and the younger generation is simply not coming back. This drives Henriquez’ passion to make the best indigenous wines he can.

Keep old-school Chile alive and start with Roberto Henriquez wines. Maybe one of the best white blends I have ever had is his blend of Moscatel, Corinto and Semillon – Rivera del Notro Blanco. His Rivera del Notro Tinto – 100% País and his País Pipeño Sta. Cruz de Coya are delicious wines that speak to his persistence and passion.