The Red, Yellow and Green Revolution

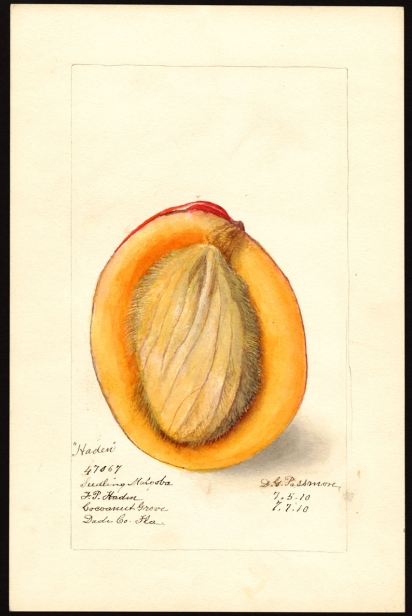

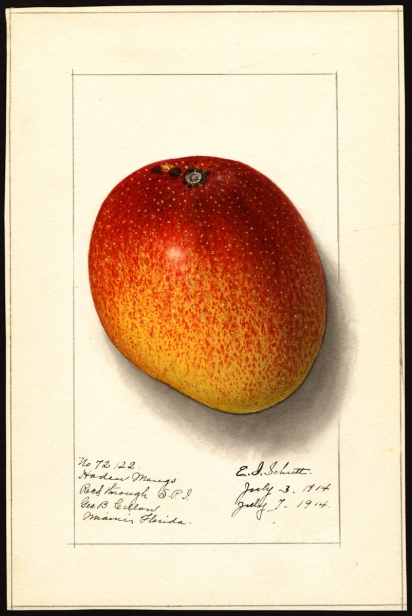

There were ‘Haden’, ‘Tommy Atkins’, ‘Kent’, ‘Keitt’, ‘Irwin’, along with a couple dozen good, red-colored mangos selected in the 1940s and 1950s. These were the mangos created by the greatest generation. Just like that generation, they conquered the commercial world and dominated international trade for a half-century. You find them today in home gardens, and for older Floridians, these are the alpha and omega of mangos. For the new generations, however, these mangos do not resonate with their modern world. They are dated, old and common. There’s a need for diversity, for a change in the status quo.

Cracks developed in the walls built on Florida mango tradition. The ways of previous generations and, in the 1980s and 1990s, collecting, breeding and selection projects took root, namely at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, the United States Department of Agriculture and Zill High Performance Plants. Collecting ushered in an influx of genetic diversity from around the world that had not occurred in over a century. South and Central Asia, Africa, the Pacific and the Middle East all made their contributions. Diversity of size, shape, aroma, flavor, disease tolerance, tree type and adaptability were introduced. Breeding and selection focused on flavor, disease tolerance, tree size and other modern horticultural traits that were of little concern in the 1940s. The criteria and objectives of the improvement were novel and dangerous, but it was the only way to change the mango world. The revolution had begun.

Making Better Mangos

I consider myself blessed to have been at the inception of this mango upheaval. These were exciting years of scientific discovery, hard work and big risks. Most of us were not trained geneticists but horticulturists, with formal and practical experience spanning decades. We knew the value of diversity, quality and a keen eye. We also knew the value instilled by those who came before us. They had created a marvel for the mango world. We gave respect, charted our path, collected, let nature do her thing, planted thousands upon thousands of seeds. Then we began to make hard decisions about who stayed and who did not. We knew that we needed a better eating experience: more sugar, less fiber, more diversity and greater risk.

It took many years. There were many failures and a few successes. Now throughout South and Central Florida, farms market ‘Coconut Cream’, ‘Orange Essence’, ‘Nectar of Neptune’, ‘Diamond’ and ‘Big Saturn’. Internet sites abound with tasting parties, expert analysis and even conspiracy theories. The proliferation of new cultivars seems sudden, but it was not. For every ‘Martian Pride’ or ‘Orange Sherbet’, there were thousands of cut-off stumps of the ones that didn’t make the grade. Setting strict objectives, using fresh eyes and letting many go was the key to success. Websites, chats and message boards are all for the good of the edible community because now we won’t settle for ‘Keitt’ or ‘Tommy’. We can have a ‘Bolt’, a ‘Montego’, even a ‘Pina Colada’. We can argue about names and tastes, but at the end of the day each and every one will trump what we had.

New Traditions

For the newcomer, the transition to mango diversity is not traumatic because there’s less traditional mango memory and resistance to change. In order to educate someone in middle America to eat a ‘Mallika’ it comes down to education. Put a ripe, high-quality fruit in front of them and they’re hooked. In contrast, if dealing with a consumer with roots in Ratnagiri, India, for instance, substituting an ‘Angie’ for an ‘Alphonso’ is much more daunting. ‘Angie’ was selected for its adaptability to South Florida, while ‘Alphonso’ suffers greatly in our humid climate. Tradition must be addressed before moving forward. Today, quality ‘Alphonso’ is hard to come by in South Florida, but ‘Angie’, a wonderful alternative, is becoming a reality. Alas, traditions die hard and a mango consumer’s memory is long.

Our current pandemic has shown that we live in extraordinary times, with electronic evaluations, opinion and access to a world of mango fruit and information, all for pickup. South Florida is once again at the forefront of the mango world with ‘Angie’, ‘Mallika’, ‘Fairchild’, ‘Ruby’, ‘Diamond’, ‘Emerald’, ‘Pineapple Pleasure’, ‘Lemon Zest’, ‘Orange Sherbet’ and ‘Fruit Punch’. Confusing, yes. Disturbing, no. This is how revolutions are – chaotic, unsettling and energetic. Over the next decade we will be in a completely new place with the mango, and it will be diverse, healthy, flavorful and definitely not boring.