Waking Up Early for Whole-Grain Loaves

Before opening Madruga Bakery earlier this year, owner Naomi Harris, 28, followed a path similar to other members of South Florida’s young artisan community. Harris, who went to Miami Palmetto Senior High School and Northwestern University, where she studied political science, did some exploring. She was a WWOOFer (Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms), working on two farms in Washington State in summer 2011, and found her way to Anchorage, Alaska. Here, she started working for Fire Island Rustic Bakeshop, a small, family bakery, where she learned about sourdough production and other aspects of baking.

“I loved the experience,” she says. “I thought, when I retire, I want to have a bakeshop.”

She didn’t wait for retirement. For inspiration, Harris visited bakeries around the country – Boulted Bread in Raleigh, North Carolina; Tartine and The Mill in San Francisco – and took baking classes. Back in South Florida, she worked for Zak Stern, when he was baking his rustic loaves in Hialeah before opening Zak the Baker in Wynwood; and Cafe Curuba in Coral Gables. She thought about what she wanted her bakery to look like – “I wanted the decor to be very airy, light, welcoming and homey,” she says.

And in the rapidly growing artisan bakeries in South Florida – Zak, True Loaf in Sunset Harbour, La Parisienne in North Miami Beach, the new Sullivan Street Bakery in Little Haiti, among others – Harris saw a need for 100-percent whole-wheat, naturally leavened, nutritious loaves. When fresh, “it’s earthy, with toasty notes,” she says. To make the best crusty, robust, whole-wheat loaves, she needed a mill to grind the wheat berries into flour. She found a source in Fulton Forde, co-owner of Boulted Bread. Harris also searched for organic wheat and flour sources for her bakery products.

Roadblocks

Finding a location was one of the biggest challenges. She looked in Coconut Grove, but rents were too high. Then she found the current space – a light-flooded, spacious, high-ceilinged corner, formerly a piano showroom, in an office condo a block off U.S. 1, across from the University of Miami on a street called Madruga – Spanish for “getting up early,” appropriately enough. Still, permitting issues – a common source of frustration for business owners – delayed the opening of Madruga Bakery by months. Finally, the doors of Harris’ bakeshop were open for business, and a few months later, on a midweek afternoon, there’s a steady stream of clients: the post-workout folks from the nearby Green Monkey Yoga and Metropolitan Fitness; University of Miami students; and locals.

On the Menu

Harris’ display cases feature rustic breads, pastries and cakes, sandwiches and snacks. There are signature Sonora loaves, ciabatta – rustic flat Italian loaves named after slippers – bread and rolls, and humble round richly textured loaves. Pastries are not showy but incorporate the flavors of a thoughtful pastry chef – a brown sugar cookie made with brown butter ($2), a dark chocolate rye brownie ($3.50), a fresh fruit galette with a whole-wheat crust ($4.50). Petite frosted cakes are simple, like the Earl Gray tea cake made with honey and lemon buttercream. Old-school blueberry danish, croissants, lemon polenta cake are humble but flavorful.

There’s no pricey avocado toast here. Instead, the seasonal toast – today it’s ricotta and papaya, $4.50 – is more traditional, she says: “I want to showcase the bread.” JoJo Tea and Counter Culture coffee, plus fresh-squeezed orange juice, are on the menu. Local produce finds its way into bakery dishes when possible. Backyard mangos (her family has 144 trees) are finding their way into tarts and desserts, and she uses the Garden Network as a source for produce.

The typical day starts at 4:30am to take out the dough, start the leaven culture, feed it, shape the bread, and bake it all by 7:30am. Helping her is a staff of 17 – 7 full-time and 10 part-time. During our interview, Harris was preparing to take a few days off for a friend’s wedding, the first time she had left the bakery since opening. “I have no qualms,” she says.

Unlike some of her bakery counterparts, Harris has no plans to wholesale her baked goods. “I’m happy to see people from Coral Gables, Pinecrest, South Miami, the UM stopping by,” she says. “I want to be a community bakery.”

Grist for the Mill

At Madruga Bakery, freshly milled whole-grain flour goes into their signature Sonora loaves, rustic loaves and in smaller percentages of some of their croissants and pastries. Every two days or so, they mill the wheat kernels using a stone mill built and installed by Fulton Forde, co-owner of Boulted Bread in Raleigh, North Carolina, and a partner in New American Stone Mills. Instead of relying on predictable, homogenized products from large mills, bakers can get more flavor in their products using an in-house mill, says Forde. “[It] allows bakers to drastically increase their grain palette and in turn experiment with flavors and textures that most people do not have access to,” he says. “Fresh-milled, whole grains are very nutrient rich and do not go through the industrial milling process, which can often strip whole grains of their nutritional value.”

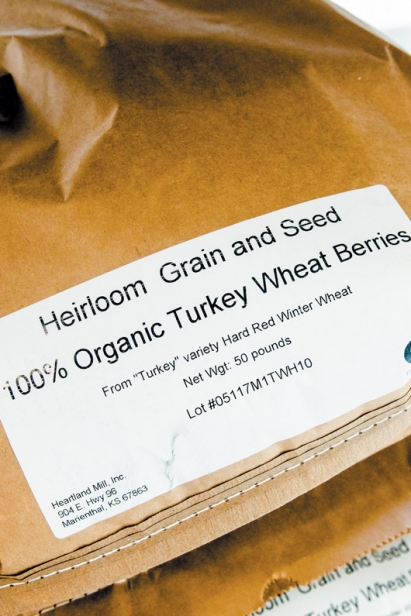

A 50-pound bag of organic heirloom ‘Turkey’ red wheat berries – once the dominant hard red winter wheat in Kansas and much of the Great Plains and now on the Slow Food Ark of Taste – goes into the hopper. Here, the berries are crushed between two granite stones, one fixed and the other spinning, an ancient technology. On the surface of the millstones are grooves cut into the stone that grind the wheat and help move it out to an opening. It will take the noisy mill an hour to turn a bag of wheat berries into flour, which contains all parts of the kernel – the nutritious germ, bran and endosperm.

After making the dough and letting it proof, Harris divides it, shapes it and puts them into pans or coiled rattan proofing baskets, where they will continue rising. Before baking in the steam-injected oven, she uses a tool called a lame (pronounced lahm) to score the top of the loaves and give them a place to expand. Then they’re ready to to bake into crusty, toasty, wholesome loaves.

MADRUGA BAKERY

1430 South Dixie Highway

Coral Gables

madrugabakery.com

Open Tues.-Fri. 7:30-5:30, Sat. 8-3