Attack of the Seminole Pumpkins

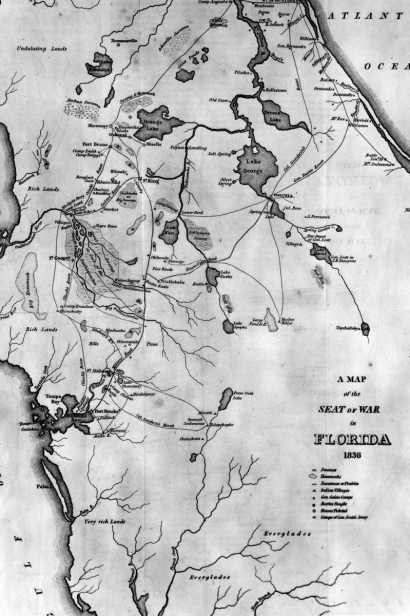

Chief Chekika traced his steps back along his original path through the Everglades muck. This had been a bold, provocative raid. When he and his small band of Seminole warriors had left the white-man trading post of Caloosahatchee, there was little left but the smoldering remnants of the houses and the bodies of fallen soldiers and settlers in the mud.

It was July in 1839. The water was high and the mosquitoes thick. It had been a summer of successful hit-and-run skirmishes and now he had orchestrated his most successful, devastating attack. Surely they would not follow, having seen his might – the soldiers of Caloosahatchee had not gotten off a single shot – but prudence and his nature drove him to be stealthy. So he doubled back and set off to their tree hammock home. This night would be a celebration among the pumpkins that hung from the trees.

Considered one of the “Spanish Indians” of the Second Seminole War, Chief Chekika had just led one of the boldest attacks in the history of this guerilla war fought in the Florida Everglades, leaving several dead. He had to be punished. Off into the river of grass a few United States soldiers pushed, led by Lt. Col. William S. Harney, still in his bedclothes. They were lucky to escape his attack and now, after a short rest, they tracked Chekika and his band for miles, losing their way on occasion. Finally, by late afternoon of the next day, they came upon the hammock only to find the dying embers of the fire – Chekika was off again. All that remained in the island of trees were his pumpkins, hanging from the trees, taunting the soldiers. Lt. Col. Harney had let him slip through his hands again. The ghost was off in the sawgrass – all that was left were the Seminole pumpkins, the food for the coming winter. No one knows if it was Harney who fired the first shot, but in the end the pumpkins lay shattered on the muck and leaf litter of the hammock floor.

Food in the Trees

In the Indian wars of the United States and countless wars before, destruction of food supplies was the one sure way to victory. The Native Americans were known to bury their gourds, pumpkins and dried meat in the ground to protect against this practice. Later they would return to these caches and thus survive the long winters. But in the Everglades, burying food was not a good option. The ground as low and mucky and whatever food was placed below ground would remain wet and surely spoil. The Seminole pumpkins, growing as a vine in the canopy above, offered an elegant solution. They would trail in the canopy above, flower, fruit and hang from the trees for the winter months. They would last for months, but they were also visible to anyone who happened upon them in the middle of the tree island.

The Seminole pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) has a rich history in Florida. It is mentioned in the expedition notes of the conquistador Panfilo de Narvaez as he marched near Tallahassee in 1528. It can be grown throughout the year and is tolerant of the insects and diseases that plague crops in the rain and heat of summer. The Seminole pumpkin will thrive under these conditions, as it vines its way up into the trees to flower and fruit. In fact, without a tree or a trellis the Seminole pumpkin will languish, flowering little and setting even less. The Native Americans would girdle large trees and plant Seminole pumpkins at their base, allowing the developing vine to scramble up the dying tree structure. Its growth is rapid and luxuriant in the late summer and fall, and as the monsoon wanes and we go into the winter, the vine will wither and die. The pendulous Seminole pumpkins turn warm amber accented with green and white. They decorate the canopy like so many tasty Christmas orbs.

Strange Fruit

You can leave the Seminole pumpkins hanging in the tree or harvest them and place them around the house and patio. They can also be harvested, cut into thin pieces and dried for later use, as our Native American brothers did. Today the harvest will be benefited by hand pollination because we have lost many of the native pollinators common during the time of Chekika in South Florida. Simply remove the male flowers and rub the pollen-covered anthers onto the receptive stigma of the female flower. The female flowers will open for a day and are best pollinated early in the morning or in the evening, when the humidity is higher and the heat a bit tempered. With a few pollination visits to your vines, there will be a healthy crop. It will also count towards your humanitarian carbon credits.

Chief Chekika remains a mystery. Little is known about him save his short but ruthless assault on the immigrant South Florida population, and his love of the Seminole pumpkin. Perhaps it was the brutal attack on his pumpkin patch that fueled much of his reign of terror. After all, the Seminole pumpkins growing in Chekika’s hammock in the middle of the Glades were innocent. Yet, they were slain, and Chekika avenged their loss upon the non-native peoples of South Florida. Of course, we can’t prove this. But I can see his point.

His encounter with the United States Army would eventually spell his demise, but the legacy of his Seminole pumpkins, born of the Glades and keepers of a rich and storied past, will live on forever as long as we grow, eat and replant them. I grew up growing Seminole pumpkins at our Homestead garden that were reputed to descend directly from Chekika hammock itself. We spent many a day wading through the swamp, my father, brothers and I, looking for the real Seminole pumpkin. We could not buy them from a seed catalog – it was a quest for the real deal. Eventually we found them (or perhaps my Dad planted them for us to find), planted them, harvested and made Thanksgiving pies and carried on the line.

Many hurricane and freezes later, I entered my 40s with no seed in hand. It took years and phone calls and site visits to get my storied Seminole pumpkins again from an old friend in the Redlands. I drag my children through the swamp on occasion in search of more genetic material, but we really don’t have to. They are in my backyard growing on top of my own girdled avocado tree. All is well in the world, except when the gun-wielding soldier takes aim at my pumpkins – but I awake, for it is but a dream and my Seminole pumpkins are safe. At least until Thanksgiving.