Can Native Oysters Help Save Biscayne Bay?

Last June’s Biscayne Bay Task Force Report sounded the alarm on the state of South Florida’s bay in crystal-clear and ominous language: “The health of Biscayne Bay remains in a state of emergency and at a tipping point toward irreversible ecological collapse.”

This crisis did not happen overnight. Naturally connected to the Kissimmee-Okeechobee-Everglades watershed, Biscayne Bay traditionally received fresh water as water moved south. As people moved to South Florida, most of the Bay’s natural tributaries were dredged and channelized, and new canals were created to carry water away from inland areas. Rampant dredging and filling radically and permanently altered how, when and how much freshwater was delivered to the Bay.

More man-made problems continue to degrade the Bay. Decades of nutrient pollution, leaky septic tanks and sewage line breaks have led to dramatically reduced levels of seagrass, the foundation of life in the Bay. As water quality declines and we lose seagrasses and document degradation of other habitats, the 41-page report warns, “the health and resilience of the Bay and our beaches will continue to decline, impacting tourism, recreational and commercial fishing and boating.”

Alberto “Tico” Aran has come up with one simple way to help tackle this massive problem: Oysters.

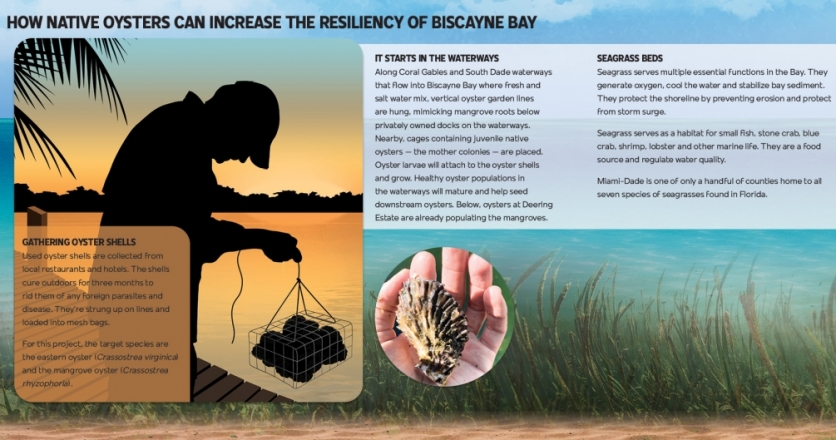

Years ago, Biscayne Bay was teeming with Florida’s native oysters, the Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) and the mangrove oyster (C. rhyzophoria). But because of nutrient pollution from fertilizer and other sources and fewer freshwater flows, oyster populations have been reduced dramatically. “Today, the oyster population is less than 1% of what it was historically,” says Aran.

Functioning as natural filtering machines, oysters are essential to the health of the bay and the seagrass. “Oysters eat algae, and we could really use that right now to help reduce turbidity [cloudiness], which would help the sunlight get to the seagrass,” he says.

Even though native oysters were part of the diet of Native Americans, Aran says his oyster restoration project is not about establishing commercial oyster farming in South Florida. Rather, it’s harnessing their impressive ability to clean water: One adult oyster can filter up to 50 gallons a day. Similar projects are in the works elsewhere to restore oyster populations, including Chesapeake Bay, the Bronx, Seattle and Hong Kong.

Citizen Science to the Rescue

Through Experiment, an online platform for crowdfunding and sharing scientific research, Aran came up with a plan to establish healthy native oyster populations along the waterways and the Deering Estate in Cutler Bay. After gathering oyster shells from local restaurants, he and volunteers would cure them in the sunshine for three months to remove bacteria. The oyster shells would be bagged up or strung on ropes to use as substrate, the surface oysters attach to, and then attached to docks along waterways. The larval oysters would grow into adults, and eventually the upstream populations will mature and help seed downstream oysters.

Aran asked for funding for permitting, substrate and hatchery raising of baby oysters. He exceeded his funding request and received the Environmental Citizen Science Challenge Grant. He presented his project to the city of Coral Gables, sponsored by vice mayor Vince Lago, who found it an ideal way to engage the community in restoring the quality of water.

“Even simple tasks can positively impact the Bay,” says Lago. “Without a clean bay, the city would suffer catastrophically.”

Aran says his two children are part of the reason he’s motivated to take action. He grew up in South Florida snorkeling and fishing, has long worked with people connected to the land, building wind turbines in rural Peru and more recently sourcing tea from regenerative tea farmers in Asia. His wife, Susan Cartiglia, is a nutritionist and yoga teacher who owns Radiate Kombucha.

“My hope is that my children and future generations have access to the beauty and bounty of the Bay as I have,” he says. “The problem is not too big for our community or us as individuals. We can work toward the future we want to create.”

FIND OUT MORE

Tico’s Native Oyster Project

watershedactionlab.com

Citizen Science

Anyone can become part of the scientific process and gain funding through crowdsourcing platforms. Aran’s project was submitted on Experiment.com, a platform for funding and sharing scientific discoveries. CitizenScience.gov is a government website designed to accelerate the use of crowdsourcing and citizen science across the U.S.