From South Florida to Senegal, lessons in culinary culture

Coral Gables Senior High School graduate Brooke Donner spent a bridge year with Global Citizen Year in Senegal.

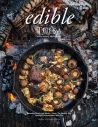

When I ride my bike into my host family’s compound in Kédougou, Senegal, after a morning spent assisting in English classes at a nearby high school, I immediately know what’s for lunch. If a pungent peanut smell wafts through the air, it’s maffe, a thick, gooey stew-like sauce served with cassava, bitter eggplant (which I find to be about as unpleasant as it sounds), and little bits of beef. If my eyes start to sting before I can get off my bike, we’re having yassa, the onion-based sauce that’s marinated in vinegar and mustard, and boiled down along with fish or meat and the best sweet potatoes I’ve ever had anywhere. And if my younger host brother is waiting anxiously at the doorway of the cooking room, I know we’re having ceebu jen, Senegal’s national dish of rice, veggies and whole fish cooked together in a tomato, onion and pepper sauce along with dried fish and sea snail.

Maffe, yassa and ceebu jen are a few of the dozen or so dishes my host mom and sister rotate around for lunch. Most are sauces served over rice with various combinations of vegetables— depending on the season – and a protein – depending on the availability. Kédougou, the region in southeast Senegal where I’ve lived since September, has its own dishes specific to its agricultural products, including peanuts and corn. As in maffe, peanuts are a main ingredient in many of Kédougou’s signature dishes, including one of my favorites, niakatan. Usually served for dinner, niakatan is made by pounding and sifting peanuts into a fine powder, which is then steamed over rice and mixed in along with onions, bitter eggplant and, sometimes, dried fish. This peanut powder is also added to laciri, a fine corn couscous eaten almost daily in many of the villages in the Kédougou region where subsistence farming is common. At my host family’s compound in town, laciri is a dinner meal eaten with maffe hakko – “leaf sauce” – and is a welcome alternative to our usual dinner of leftover sauce from lunch.

During my first few weeks in Senegal, the food took some getting used to – I was not accustomed to eating bread for breakfast, rice for lunch and rice again for dinner every day. But the act of eating required an even larger adjustment. Here’s why. If you were to walk into my host family’s compound on any given day at around 2pm, you’d find seven or eight people sitting around a large, one-inch deep circular plate set on a piece of fabric on the floor. The men would be eating with spoons, and the women and children would be using their right hands to make balls of rice to pop into their mouths, which is infinitely more difficult than you’d imagine. My host mom or sister would toss pieces of the vegetables, and fish if it was a fish dish, from the center of the plate into the section of rice in front of each person.

Conversation would be minimal, except for when the people sitting around the plate spot a passer-by and summon him or her to “come eat, please.” When someone is finished eating, he would stand up and immediately be bombarded with questions and commands from the remainder of the eaters. “Where are you going?” “You didn’t eat!” “Are you full? Really full?” To which the presumably full person would respond, “Yes, I’m full, really full.” He would then leave the eating area, theoretically to make room for someone else to sit down and eat. This would continue until everyone has finished eating, at which point my younger host sister would take the plate, spoons and bucket of water for hand washing into the cooking room, and my younger brother would take the piece of fabric over to the goat hut to shake out the rice. Lunch was over.

Afternoons around the compound are often spent hiding from the sun and listening to music while my host sister and neighbors get their hair braided or unbraided and someone prepares attaya, a loose-leaf green mint tea found in almost every home across Senegal. The attaya cooking process consists of three rounds of tea, each less bitter and more sugary than the last, and lends itself perfectly to the leisurely pace of post-meal chats with friends and family, even allowing for naps to be taken between rounds.

My host dad sometimes skips the mid-day nap and attaya sessions to run errands around town. When he returns with a black plastic bag hanging off the handlebars of his motorcycle, my host brother can hardly wait until the motorcycle has stopped moving to see what’s in the bag. Occasionally, funds and supplies permitting, there’ll be a treat in the bag, like bananas and apples, or oranges, watermelon, papaya or mangos, depending on the season, or something special to make for dinner, like lettuce for salad. My host brother occasionally strolls into the compound with a snack, such as a lollipop, an extremely hard ball of caramel, various forms of fried dough (some savory, some sweet), or a frozen sack of hibiscus or baobab juice.

When the sun has set low enough to shade the entire compound, the relaxing and chatting comes to an end, water is pulled from the wells, dishes are washed, babies are bathed, children are sent to nearby boutiques and tables to purchase ingredients for dinner, and cooking preparations begin. The eating process repeats itself for dinner, more attaya is made, and conversations from the afternoon are continued into the evening, only to be carried on to the next day when we do the whole shebang over again.