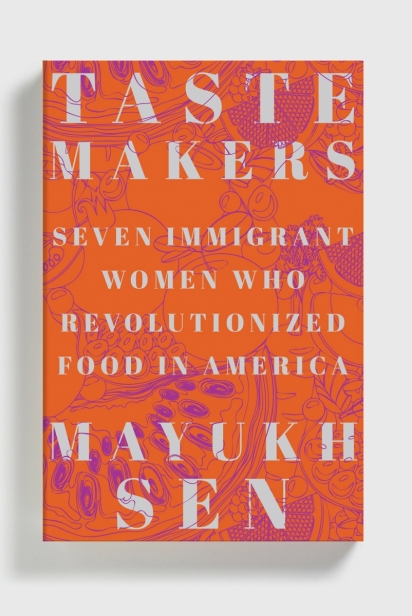

Taste Makers: Seven Immigrant Women Who Revolutionized Food in America

Sen’s new book, Taste Makers: Seven Immigrant Women Who Revolutionized Food in America, focuses on seven women who came from elsewhere, bringing the foodways of their homes and changing American cuisine forever.

Good thing, because before their arrival, 20th-century American food tended to be heavy and tasteless. More than one of the women in Taste Makers found it disgusting. America didn’t like what these women cooked, either, at least at first. Sen’s first profile looks at Chao Yang Buwei, “arguably the first Chinese cookbook author,” who helped make Chinese food accessible and desirable. He profiles Marcella Hazan, who became the authoritative, unflinching voice of Italian cooking, and Indian cookbook author, teacher and restaurant chef Julie Sahni. Another woman featured is Norma Shirley, who shone a bright light on Caribbean cuisine, not as a cookbook author, but as a chef in various restaurants “bringing food with a Jamaican flair to a wider audience.”

For Sen, food is more than an Instagram post. “Food tells us a lot about ourselves,” says the Food52 alumnus. “Where a person comes from, the culture, the values they hold dear, the inequities they grew up with, who cooks in a family, how that culture treats women. Food touches every aspect of human life.”

A food journalism professor at NYU, Sen has earned numerous food writing awards, and he’s only 29. Yet he often feels like an outsider, much like Shirley and the other women of Taste Makers. He identifies as queer. “My parents were immigrants from West Bengal. I grew up in Jersey,” he says. “I have an anxiety for women like the figures in the book, for the challenges Black and Brown women face.”

Norma Shirley, profiled in his book, is familiar to many in South Florida as namesake of Norma’s On the Beach, the South Beach restaurant opened in the mid-1990s by her son, Delius Shirley, and chef Cindy Hutson. Born in Jamaica’s Saint James Parish, Shirley trained and worked as a nurse, and married a doctor. The family settled in the Berkshires, and Shirley, with no formal culinary training, began catering out of boredom. What she had was an artist’s instinct. “My mother didn’t think about basic,” says Delius. “She wanted more interesting things.” So she created them.

With a partner, she opened the Station restaurant, dazzling locals and food media. But the Berkshires were cold. And White. Shirley was “a Black woman,” says Delius. “She was point one percent of the population. “She didn’t feel wanted.” New York in the 1980s proved no more welcoming. Shirley had talent to burn, but her marriage had ended, she had no contacts, capital or investors. The food establishment didn’t know what to make of Jamaican food or of Shirley, with her bright head wrap, hoop earrings and jangling bangles. Instead of opening a restaurant, she became Condé Nast’s caterer, cooking for celebs. There she perfected her own vision and style, treating tropical produce to classic culinary techniques. She pioneered the New World cuisine that put Miami on the foodie radar with White chefs like Allen Susser, Norman Van Aken and Ortanique’s Cindy Hutson. “She urged me to expand my palate,” Hutson says of her mother-in-law. Shirley also taught Hutson how “to turn food into art,” like nestling curried shrimp inside papaya.

That Vogue called Shirley the Julia Child of Jamaica was meant as a compliment, but “it feels so flattening,” says Sen. After enduring struggles and slights, Shirley decided she’d had it with New York. “She said, ‘I miss home,’” recalls Delius. “She always wanted to make the country better, to help people. This was her opportunity to share with Jamaicans what possibilities are out there, to go back and cook for Black Jamaicans.”

Shirley returned to Jamaica in 1992. “Her primary goal,” writes Sen, “was to get Jamaicans to see their food with pride.” She succeeded. Locals flocked to her restaurants. They valued Shirley and her cooking in a way Americans didn’t – except in South Florida. Shirley’s Jamaican flair found a home at Norma’s on the Beach. Run by Delius and cheffed by Hutson, it was a hotspot back in 1994, Lincoln Road’s artsy, funky days. From there, the couple brought Caribbean to Coral Gables with Ortanique. Its signature salad, Norma’s Terrace, with hearts of palm, ribbons of mango, and a zippy passionfruit vinaigrette, was pure Shirley.

Mayukh Sen’s book provides a taste of each woman’s victories and struggles, but not a taste of their food – there are no recipes. “No one recipe can contain the fullness of each of these women,” he says. “Food as mere entertainment has eroded a lot of respect for people who labor over food all the time.”

Eroded, indeed. Shirley and the other women of Taste Makers worked hard to earn a degree of acclaim in their day, yet America has largely forgotten them. “I found it so scary, this work you do can be overwritten,” says Sen. “American food media’s attention span is so short, and we forget so easily.”

Find Taste Makers: Seven Immigrant Women Who Revolutionized Food in America at Books & Books or your favorite bookseller.