Where My Ladies At?

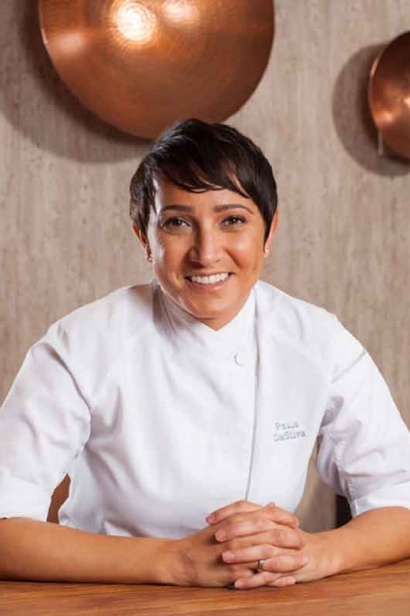

The year was 2008. Michelle Bernstein won the James Beard Award for Best Chef: South. Cindy Hutson’s Ortanique in Coral Gables already had a decade of accolades for its soulful Caribbean cuisine. In Fort Lauderdale, Paula DaSilva was honing her skills at 3030 Ocean, having started as a line cook, and would later return as executive chef. And in a strip mall in Kendall, a 23-year-old Johnson and Wales graduate’s restaurant, Chef Adrianne’s Vineyard Restaurant and Wine Bar, already had a year under its belt.

What a difference a decade makes.

In 2018, the competitors for the Cochon 555 in Miami, celebrating heritage pigs with cook-offs throughout the country? Five men, one woman. The rollout of chefs for the long-awaited Time Out Market Miami? Eight guys. In a June Miami Herald business story on impressive South Florida restaurant groups, the management teams are all male. If you’re a young chef searching for women role models in the kitchen, you have to look hard.

“I don’t see enough of us; I never have,” says Bernstein, whose business includes Crumb on Parchment in the Design District, catering and appearances. “Throughout my whole career, I’ve hoped to find more women to share the kitchen with. I’m not saying we are not a powerful bunch, but when you compare the numbers, it really doesn’t make any sense.”

Some restaurant owners in South Florida say that for every 10 applicants for line cooks they interview, only one is a woman. Sometimes they get no female applicants at all.

“I just had this conversation with Lindsay Autry yesterday,” says Bernstein, referring to her former colleague who is now chef of The Regional Kitchen and Public House in West Palm Beach. “She is having a very hard time finding cooks and chefs that have staying power. Someone that will really sink their feet in and work hard, without worrying about ego, taking direction from a strong woman. I told her to find a good woman chef/cook. She told me none apply. That they never do. I rarely have any applying with us either.”

Many of South Florida’s culinary leaders, including Bernstein, Autrey and Calvo, graduated from Johnson and Wales University in North Miami, where the culinary student population is evenly divided between men and women, says dean Bruce Ozga. “Our population is 50/50 culinary and pastry,” he says. “Pastry is predominantly female.” But not everyone who graduates ends up in a restaurant kitchen, he says.

“If you ask at orientation how many students want to start their own restaurant, you get a lot of hands,” he says. When you get to graduation, that number goes down. Many of their graduates have chosen less-visible careers. “Some of our grads are not going into restaurants and hotels. They’re choosing personal chef, catering, R&D, food manufacturing, a lot of other divisions.” Restaurant work is more challenging, the hours longer, the pay lower, he says.

If you can’t stand the heat…

“Grueling” is a word frequently used to describe work in a restaurant kitchen, no matter what your gender. “The kitchen has never been a politically correct environment,” says Adrienne Grenier, executive chef at 3030 Ocean, who began her career under Dean Max and Paula DaSilva. “It’s not about being male or female. There’s so much work, you have to be mentally and physically strong. It’s a lot for anyone.”

“It’s hard,” admits Hutson, whose businesses today include two Ortanique locations and Zest in downtown Miami and Negril, Jamaica. “I’m busting my ass 17 hours a day. My arms are scarred.”

Now, consider how much harder the job for a woman when her male colleagues act like jerks. “I still get bullied in the kitchen,” says Calvo, who is frequently the only woman chef on the roster at charity events. “It’s a good old boys’ club,” she says, where she’s still told: “Let the big boys take care of it. You can’t talk shop with us.”

“I do remember early in my career, the guys would try and push the women to see how far they can take jokes and pranks,” says Tara Abrams, executive chef at Crazy Uncle Mike’s, who has worked her way up the ladder at multiple JEY Hospitality Group restaurants.

Women chefs put up with everything from sexist words to worse actions from male counterparts. “You can tell when males working below you have issues with a female in charge,” says Nicole Votano, 36, who’s worked in a number of Miami kitchens in recent years. “They’ll say, ‘she’s bitchy’ – no one ever says that about a man.” Camila Ramos, 30, co-owner of Miami coffee shop All Day, recalls being asked to smile more when she worked as a mixologist. “Women are smiley, happy creatures,” she says. “Men are serious and professional.” At her business, she adds, “everyone needs to smile – it’s a requirement.”

It can get worse. Some female chefs report butt-grabbing; one says a male chef once grabbed her in the walk-in, so she punched him in the face. He didn’t bother her again, she says.

Bad behavior must not be tolerated, says Bernstein. “I’ve never allowed any type of toxic behavior; male or female. No one stands for it anymore. It’s too costly (reputation and otherwise).”

It’s also against the law, says Lisabet (LB) Summa, executive culinary director of the Big Time Restaurant Group, and co-chef and partner with Louie Bossi. “It is illegal for a guy to treat you poorly or make you feel uncomfortable. That behavior in the kitchen is not tolerated,” she says.

Better together

One of the ways to make the kitchen workplace less fraught with toxic masculinity may be, simply, to seek out other women and hire them. Jorlian Rivera, 32, is the executive sous chef at S3 in Fort Lauderdale, having worked her way up the ranks under Chris Miracolo. She’s kept 90 percent of the women she’s hired because she finds them to be hard workers and dedicated, compared to some of their male counterparts who are “just here for the paycheck, or to find women,” she says. “The easiest way to tell is when they start flirting with you during the interview. Women sell themselves on what they’re good at. It’s not about who’s better – let’s be better together.”

For Ines Chattas, who opened Open Kitchen, a neighborhood restaurant and catering company, in 2011, women have proven to be more loyal to their jobs. “My longest-serving staff are women,” she says. “Men always looking for the next opportunity.”

But Hutson finds differences in younger women candidates, including millennials, who have “excellent cook potential” but less humility. “Women of today in culinary are not like my age group. They feel more entitlement, they’re harder to mentor because they see criticism as disrespect.” In her kitchen, she has hired older women who are “cooking for pleasure. They’re great home cooks. And I’ll get more women who see I’m a woman.”

Creating a better environment

The restaurant kitchen where pans are flying and cursing is rampant is on its way out, at least in some kitchens. “Old-school management with verbal abuse was unhealthy,” says Camila Ramos. “Men are trained to take it. But we’re wired differently. We may be physically and psychologically different, but we should all be allowed the same opportunities. I think the conversation is: What does equal opportunity mean? How do I create an environment that’s fair for both?” South Florida women in the business offer these recommendations:

Set up guidelines on acceptable behavior – and enforce them. This is essential, says Jackie Pirolo, managing partner and beverage director of Macchialina in Miami Beach. “Things have to change,” she says. “We’re very strict. We have staff meetings reviewing policies and examples – that sarcastic remark is not OK. We have an open-door policy. You can text, call, write a note if there’s something uncomfortable going on.” And, she adds, be strong enough to make yourself heard. “You have to assert yourself early on.”

Look for mentors – or be a mentor. This has become important to Paula DaSilva as she approached 40. “I want to mentor my staff,” DaSilva says. “Nurture our industry. Give guidance. I thrive on positivity.”

Present alternatives to unhealthy behavior. After-hours drinking for the staff isn’t the only way the staff can unwind. “Wellness is more important in the industry,” says Grenier. “In my kitchen, people are going to the gym after work instead of bars.”

The time? Right now

All the stories about toxic workplaces for women in the kitchen have led to an awareness that has resulted in much better working conditions for women, says LB Summa. “In a kitchen you’re going to be treated better,” she says. “I can’t think of an industry that is more hospitable to women in South Florida right now.”

Dean Ozga of Johnson and Wales agrees that demand for culinary workers is sky-high. “We get calls daily. We need people,” he says.

And opportunities abound, even for the untrained worker, says Summa, creating “an amazingly fantastic, potent opportunity for women in South Florida right now. The pay is $12-17/hour right now without experience. You’ll get a meal, taught a trade or skill that will serve you. I’m hiring sous chefs. It is easy to get a job.”

Summa is more bullish than ever about the industry welcoming women in the restaurant kitchen. “I love this profession,” she says. “I love being a chef. We just need women to show up.”